The Zip: Episode 31

The expression ‘quarter life crisis’ is often said with a sort-of smirk. Like it’s a joke – oh, you know, those young people with all their “problems.” I spent my quarter life crisis trying to write a screenplay, and probably spending too much money on wine. It feels sort of silly. You’re so young, of course you’re lost. Of course you don’t know what you want from life. Of course you make bad decisions. But that smirk, the joke of a quarter life crisis presupposes a few things. It assumes that the person in quarter life crisis has a degree of stability, that they’re probably a clothed and fed and probably well-educated twenty-something who just isn’t sure how to ADULT yet. A recent college graduate shocked at the sudden tedium of a 9 to 5. Or a 24 year old with relationship commitment issues. Many of us have been there. It feels serious at the time. But we know it’s out-grow-able. Because most quarter-life-crisis are signs that we’re growing in the right direction – it means we have that job, it means we’re seeking and forming relationships.

But what about our young people who don’t have that stability? What if you’re trying to figure out who you are and how you fit into the world, from the streets? Simultaneously charged with shaping your personality and setting a course for your future, while still having to worry about where you’ll sleep tonight?

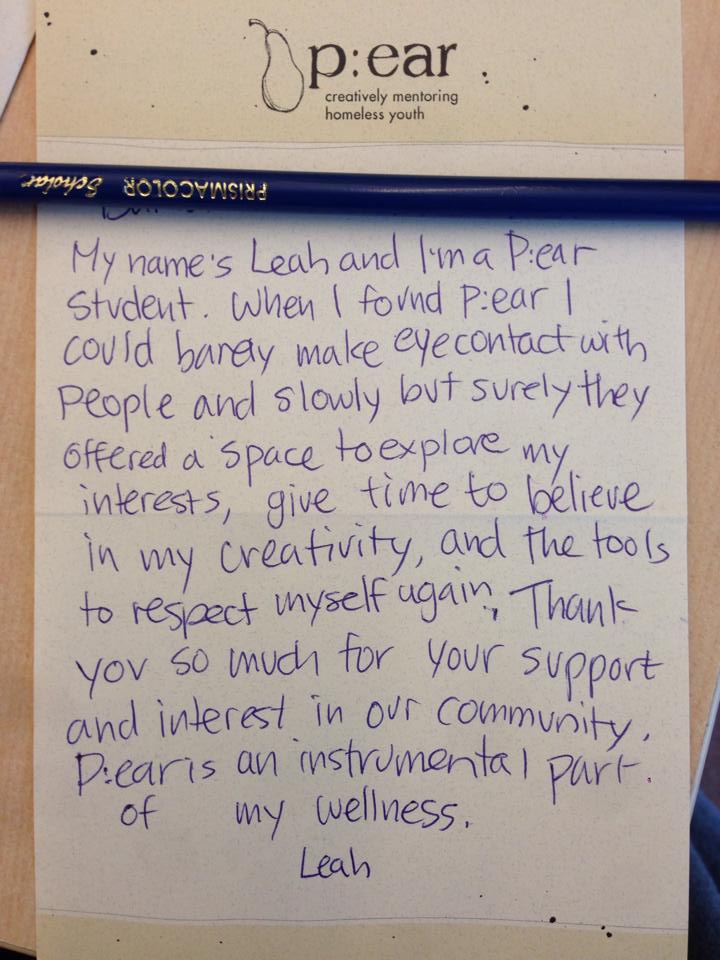

Homelessness is a tragedy at any age. But for the young – to be so early in life and already feel like an outcast, I think it can be particularly damaging. Which is why I loved hearing from today’s guest, Pippa Arend, who works to change the lives of homeless youth.

Portland native Pippa Arend, spent her quarter life crisis seeking – not self actualization, but accountability. And out of that quest, with the support of a couple partners, came P:ear, a Portland nonprofit that creatively mentors young people, in real-life crisis.

So let’s jump in.

Welcome to The Zip.

Megan Hannay:

Pippa, thank you so much for being on the podcast today.

Pippa Arend:

Thank you for having me.

Megan Hannay:

Absolutely. Can you tell me a bit about p:ear? I know your mission is about creatively mentoring homeless youth, but there’s so many parts of that I want to break apart and understand better. I guess maybe even the most obvious, if not naïve question is, why do we have homeless youth here in the U.S. in the first place? Why are there young people on the streets?

Pippa Arend:

Well, that’s a really big question. One of the questions I can answer, which is what we at least do and even what the acronym is, p:ear stands for Project Education, Arts, Recreation. We’re working with 15 to 24 year old homeless kids through those tools. So, it’s through the tools of the head, through the tools of the heart, through the tools of the body. To go into larger questions about why there’s even homeless youth on the streets at all, it’s something as we head into our 15th year, I’ve been thinking about it a lot. In my travels to other countries, and I talk with young people or adults, often when there’s an experience of homelessness in other countries, it’s due to war, it’s due to bombings. It’s due to the loss of the house, due to some terrible situation. In America, we’re dealing with young people that are homeless not from war but from poverty or from lack of attention from parents. There’s often a myth that kids are runaways, especially in the West Coast here. There’s an idea that kids are on the streets because programs make it easy and relatively safe for young kids to be on the streets, and that is just not what we’ve found. In the 15 years we’ve been around, we’ve enrolled about 5,000 kids, and I’ve seen maybe 10 parents. These are not kids that have parents looking for them that we see. I sometimes think of these kids as not at-risk. They’re post-risk.

Some risk already happened to them where they found themselves not only without a home, but without a relationship that would allow them to have a home, that would allow them to be supported. Often, we find kids that have experienced terrible abuses in foster care. Foster care is great when it works. When it doesn’t work, then those kids are my kids. We see kids who, there’s just no room in the trailer for them. Right now, in 2017, we’re eight to 10 years after our great recession, and I think there was a lot of families that had a lot of kids. They’re five or six years old, maybe 10 years old eight or 10 years ago, and their family went through some real hard times. It’s certainly unemployment, and add on top of that the rise of methamphetamine use, and get a perfect storm where there’s instability in a family with young children. Ten years later, those kids are on the street. So, those are the kids that we often see and that we’re working with here. The answer is sort of a broader array of your questions.

Megan Hannay:

Yeah. You actually cofounded p:ear. How and when did you first learn about and start caring about homeless youth? What personally for you really brought that to your attention?

Pippa Arend:

My background is in the arts. Our motto is creatively mentoring homeless youth, as you mentioned in the beginning. We actually look at that word creatively as much more than arts. We look at it as simply being able to respond interestingly or creatively to homeless youth in any adverse situation. Creatively mentoring homeless youth could be using math as a tool for engaging a kid who has some behavioral issues. Or using food or whatever tools are at our disposal. That’s how we use this word, creatively. That said, my background is in the arts. Visual artist as well as a welder. Arts are one of the main tools that we use to work with these young kids. We certainly have a GED program, a high school accreditation program for these kids. We have a bike mechanic school, a barista school. So, several job training programs, but our gallery, we have an on-site gallery where the kids and show and sell their work and keep 90% of the proceeds. And we have a fantastic arts coordinator, a guy named William Kendall, and he leads our music program as well.

The arts are one of the main tools that we use to engage with young people, in part because it’s so safe. It’s such a safe way to interact with colleagues. There’s nothing like working on a project that doesn’t necessarily have an end in mind, some kind of artistic project where the process is really what’s interesting. Doing it with someone, two people who maybe come from really disparate backgrounds working together on some common project, there’s nothing like that to create communities. That’s really how and why we use the arts and certainly, that’s where my interest comes in.

And to get to my story personally, honestly, I was in the right place at the right time, because I was a young welder and in my mid-20s and having a mid-20s great kind of life, but I at a certain point, looked around and realized I was missing something in my small young business, which I finally was able to put the word on, which was accountability. Specifically, accountability to my community. I started looking around for ways to use my arts skills, which at that point was pretty extensive in terms of knowledge of how to use materials.

Through a friend of a friend, met a woman named Joy who was running a Salvation Army run program for homeless kids, a school. Her and the woman who ran that school with her named Beth, they were looking for an arts person to come in. That wound up being me, and within about a year, that program folded anyway. There I was with these two really amazing women who had deep knowledge of working with homeless kids in this kind of environment. The three of us, when that other program folded, we decided to replicate the best parts of that program, the relational piece of that program, and make it better and make it more holistic, and again, bring it not only the intellectual pieces, not only the emotional artistic pieces, but make sure the body was included as well. Again, that’s the acronym. Project: Education, Arts, Recreation.

Megan Hannay:

Yeah. First of all, that is a super, I feel like, profound insight for someone to have in their mid-20s. I feel like in your mid-20s, sometimes it’s enough to be figuring out who you are and what you’re doing in the world. So, to have that realization of needing accountability, that’s pretty impressive. After the Salvation Army program ended and you guys decided to make p:ear, what were some of the lessons you learned as far as things that you did and didn’t want to take specifically from the program that didn’t work out?

Pippa Arend:

One of the things that we did not want to take with us from that other program was how that other program ran their food program. They took donations, of course, but often the donations were beans and weenies or what we call potato poopies.

Megan Hannay:

Gross kind of—

Pippa Arend:

Just gross. Not only gross, but high fat, high carb. Foods that really perpetuated cycles of poverty, obesity, and also set up kids for failure in terms of being able to pay attention. Often, these kids are sick. They’re sleeping outside. Half of them have walking pneumonia on any given day. We have kids today hacking up a storm. They’re ill, they’re tired. They’re bodies are growing. They need a lot of solid, good nutrition. They’re teenagers, and many of them have a lot of food sensitivities, sensitivities to gluten. I’ve seen kids who were Celiac, and the only choices available for them were mac and cheese and bagels. Yes, they ate those things, and then they would pass out because that’s what happens. Then, they would get in trouble and kicked out of that program for sleeping. We wanted to rewind all that and try to really think through it.

What we created in our space, we’re located on Northwest 6th and Flanders, Portland, Oregon in Old Town. We have a large space, and in the center of it we put a kitchen. We connect with many, many, many local vendors, purveyors, food stores. In the beginning, it was real humble. I would call my mom. The guy I bought my truck from whose family owned a restaurant, we would call these people and they would make sandwiches or burritos for us or whatever we could in the beginning.

This year, at this point 15 years later, we have a kitchen and we get donations from a great nonprofit called Urban Gleaners. They go around and pick up food and instead of thrown away, gets used by people that can use it. We work with New Seasons, Whole Foods, great local restaurants and put wholesome food at the center of our program. We always have food out. Another thing that we didn’t take with us is this idea of, you have to eat at 9:30 and 11:30, which is sort of prison style. We always have food out. These kids, they don’t have regular schedules. Their schedules are erratic. We just have food out. It’s warm. They can eat it. Then, we can move on into the other programs of the day. Food, we feel, is a fundamental right, and we try to make it as wholesome and as varied as possible to really accommodate the different kinds of kids that we have.

What we did take from that program that was super important to us was this idea of relationship. That program had some pros and cons to it. One of the pros was that it had a real stable staff that had been there a very long time, often for at least a decade. The staff were able to make deep and profound relationships with homeless teenagers. It was through those relationships that we really saw the transformation happen with each individual young person. When that program shut down in Portland, there arose a model of cycling through putting homeless kids into what’s called the continuum with giving them a case number and processing them through as though you can just plug in x, y, or z and the kids come out the other end more wholesome. Sure, that works with some kids, but we found for the most part what the kids really needed was that relational piece. So, we’ve taken great pains to hire very slowly, but to hire in the long term. We’ve grown our staff now to nine people, many of whom have been here for years at this point. Our volunteers make a commitment for a long time. So, they give real stability in the actual relationships with the young people because again, that’s the only thing that helps people change, is having that sense of witness and personal care.

Megan Hannay:

It sounds like you guys have set such a high bar for standards for your organization. Was that difficult in the beginning when you’re just fundraising and like you said, you called your mom to make burritos or whatever. I feel like when you have money, it’s easy to set standards, but when you’re just starting and you’re scraping something together, it’s the take what you can get, beggars can’t be choosers mentality. Have you incorporated these standards over time? Or is this always been something like, no, we’re going to do this right?

Pippa Arend:

First of all, I love these questions. Thank you, Megan. I think we just didn’t even think about it. Of course we did, but it was just intuitive. We didn’t want to compromise. We had a vision that was real clear from day one of who we were and how we wanted to work with these kids. We had the good fortune of being in our late 20s and early 30s in the beginning, meaning that we had a lot of just physical energy. We could work long and hard hours and drink a lot of wine. The fuel for the early years of this program was wine and chocolate.

Megan Hannay:

Wine and chocolate, and coffee in the morning. Wine at night.

Pippa Arend:

Yeah, and stick in some French fries. That was our fuel. Beth and I were both late 20s, early 30s in the beginning of this, and Joy, the third of us, was mid-40s. Thank God, because we had this age range and stability through her. She was really the one that had the maturity to hold the vision, and then Beth and I had the youthful vigor to go to every fundraiser, to just go out every night, every weekend and just hustle and connect and network and figure it out, see how it’s done. That was the beginning piece of how we began to think about it. It took a lot of time. We didn’t pay ourselves until year three. It was lean years in the beginning, but again, we had that drive and vision.

We also formed about two months after 9/11, and this is significant because if you remember that time, it was such a tragedy for our country and the world. The epic proportions and there was something in the air that was really collegiate and collegial. As we were forming p:ear, there was a lot of people that we felt had our backs. There was a lot of people that stepped forward to help in terms of mentoring. How do you start a nonprofit? We didn’t know any of these things. How do you do a fundraiser? We didn’t know. What we did know is how to work with young people. So, that’s what we did and let the momentum build from there.

Megan Hannay:

Yeah, that’s cool. You mentioned that you have arts programs, you have GED programs, and you also have, I was reading on your site that you have a barista program and a bike mechanic program, which take a couple months each to train young people with skills so they can find an entry-level position in these fields, which I think is such a cool—they’re getting something out of it. They can get a job. How are you able to funnel some of your program participants into these areas? Do they have to be in your program for a while? Do you see kids and you’re like, this person would be great for the bike mechanic program? How does that work? What is the typical path for someone who’s in your program?

Pippa Arend:

Our space is not big. It’s a quarter of a city block. So, just a corner. We have two main areas. One area we call the Great Room, and that’s where the bulk of the action in any given day happens. Then, the other room of equal size that’s through a passageway is what we call our gallery, and that’s where we do first Thursdays and what have you. It’s also where we have built in our barista school. We actually have at this point an externally facing window because they’re working it right now. We have an actual social entrepreneurial business operating out of our gallery window selling coffee to the public. Then, our bike mechanic school are two pods. By that, I mean these structures that get pulled out on Wednesdays. Recently, because we’re just in our second semester ever of our bike mechanic school. It’s a very new program. Those open up in our gallery space, and then the four kids who are in that program starting working on bikes with the teachers that are here. I say all that because it’s all happening here. Kids self-select, essentially. Because it’s a relationship based program, if I know Sally is mechanically inclined, I can say, hey Sally. Bike mechanic school, third semester starts March 3rd. What do you say? I think you should sign up. It’s really as organic as that.

Megan Hannay:

That’s cool. I was reading also an article in which those talking about these programs where you were interviewed, and you said a really interesting quote that I want to ask you about. You said when a kid is doing well, that’s ironically when they need the most support. When they’re struggling, you provide safety and food, but when a kid is starting to bloom, to change internally, to become a member of a community as opposed to a Portland street kid, that’s when active, creative support is most needed. Can you unpack that a little? Because I thought that was so interesting. Do you see a lot of situations where young people in your program start to succeed and then fall back? Do you guys have ways of helping people through that?

Pippa Arend:

Sure, yeah. That’s the entire value of the program, to help kids hold onto something once they have something to hold on to. If you think about it, the kids who come into just our basic program, which we call Safe Space. They come into the Great Room, they just met us or they’ve been coming here for a couple years, doesn’t matter. They come into our Safe Space and have food and sit with other people. If they don’t have anything to lose, they’re just on the streets where there’s nothing, really there’s only one way to go, and that’s up. We can provide kids with resources, or if they need mental, dental, optical, food, clothing. People that know their name, people that care about them. Just build them up to a place where they can start, maybe engaging them in workshops or taking a little bit more care about themselves. Or maybe starting to self-edit or just take those small developmental steps towards maturing. At a certain point, when one kid is interested in our job training programs, the barista school, selling art in the gallery, the bike mechanic school, we have p:ear barista now. We also have a new high school accreditation program I was talking about.

When a kid has something, responsibility to show up for the p:ear barista school, or maybe not they’ve been given an apartment. They have some kind of housing through some kind of voucher program. Now, they have something to lose. What we find is that’s really the most precarious time for a young person. It’s when they run into issues of self-doubt. Am I worth it? All those foundational places where they feel unworthy. Really, don’t we all? We all have these issues, but compounded. Just imagine yourself as having those issues but now you’re a homeless teenager and you didn’t have any parents who cared for you, or at least for the past 10 years and you maybe have been exposed to some street drugs and maybe you have prostituted yourself in order to survive. You’ve compromised your personal sense of self or sense of integrity. As you start to have something to hold onto, all those issues start to come up. It’s a time of great self-sabotage.

We’ve seen it over and over again. Again, in relatively mentally healthy people, but especially in homeless teenagers. Our primary value is in creating community for these young people and developing relationships with these young people. It all comes back to this so that these kids can have this foundation, develop a foundation of self-worth and then from there, grow themselves. As they start running into their demons as they are maturing, these are rightful stages to go through, all these stages of self-doubt. We’re there for them. It’s that internal development that gets so disregarded in most programs, but it’s really, it’s the pay dirt. Without that internal maturation and development, no one can hold onto anything. These kids can’t hold onto anything.

Megan Hannay:

Right. That makes so much sense, because I think there is that moment. Any time I think, even if you’re in a different situation, there’s that pressure. The more responsibility you have, suddenly it’s like, can I handle this? I can see how that would turn into, if you don’t have people reinforcing, yes, you can handle this. Yes, you’ve got it. That can, on a bad day, backfire. That’s really cool. Pivoting a little bit, I’d love to ask about your fundraising efforts. Obviously, you guys have been going on for 15 years. So, I imagine you’ve done a lot. You said at the beginning, you networked a lot. What has that process been like? What kind of sponsorships do you have now? Are they mostly grants or do you get a lot of corporate sponsors? What is that area like for p:ear?

Pippa Arend:

I think we’re in a really unique position in having primarily individual support, which is pretty unusual. We decided from the beginning not to take any county of federal funds. In part, those get cut as we have seen recently on a large scale. But even on a small scale, city and counties, the budgets fluctuate. We didn’t want to be subject to that. We also didn’t want to buy into the local system, which is called the HMYS, which is a database that takes a couple staff people to run. When you take that kind of money, you’re often in a position where you need to fulfil x, y, and z for your donor. It makes sense, but it can sometimes run counter to the needs of the young people that we’re serving. We had seen that firsthand at the other program that we came from. That’s another piece that we didn’t want to take because when we were running that other program, we saw really directly how there can be conflicts between what the students needed or what the donating organization wanted the kids to do.

It was again more interesting to us to take fewer funds if possible, but have those funds grow stably so we could create stability in programming for our kids so we wouldn’t have to ever be in a position of taking things away. We could just slowly build, slowly build, slowly build. I think it’s been really successful. A piece of that that’s really funny is during the recession, when many nonprofits locally and nationally were complaining about the loss of corporate dollars, we looked around and we noticed that we didn’t lose anything, and that we in fact grew a little bit that year. We realized, that was awakening into corporate dollars. We were like, oh, right. We had never gone after corporate dollars. We didn’t know about them. We didn’t think about them. We’re not trained in these areas. It was as we started coming out of the recession that I really personally took that on as a thing that I wanted to do and start figuring out, how do you get corporate dollars? We’ve grown that piece of our support. It’s not huge, but it’s sizable at this point, and it’s from some of the usuals, like Standard Insurance has been a long, steady supporter. Some of the big ones, but what I love about who supports p:ear and the businesses and corporations that support p:ear is, often it’s the small ones or the obscure ones. For example, William Henry, they make men’s jewelry and custom pocket knives that are gorgeous. That is just beautiful materials. They just took it upon themselves to start giving 5% of their online retail sales to us.

Megan Hannay:

That’s amazing.

Pippa Arend:

It is not a small amount. It’s just because the CEO believes in p:ear. They’re not alone.

Living Room Realty, a local real estate company, they give 5% of their profits to three nonprofits that their agents selected. We’re one of them. Some of them are one-offs, but it’s people, not corporations. It’s the people in these businesses, corporations that get it, that get this idea of local support for the work that’s being done that’s good, that they believe in. That’s that part. Then, of course, at this point, there’s family foundations and we do one big gala per year that raises about a third of budget as well. That’s coming up in April. I run that.

Megan Hannay:

That must be a lot of planning.

Pippa Arend:

It is a lot of work, yes, but it’s fun. I get to engage with a lot of local businesses who donate or give at a great price. For example, Owen Roe Winery, which is one of our great local Yamhill wineries, they donate all the wine. It’s just so lovely. It’s a great way to interact with our community again.

Megan Hannay:

Yeah. That’s really cool. I love hearing all the different ways that sponsorships can be found through organizations. I feel like it’s an interesting way of putting things together, and different organizations have such different strategies around who they’re going for. Finally, on the podcast, I love to ask people a bit about where they’re from since the podcast is about locals. So, you’re from Portland, I believe. According to your bio, you left for college and then came back. What is it about Portland that draws you in? Then, with Portland in particular, because I feel like it’s one of those cool cities to move to right now, but as a native, how do you see the city in a way that others may not see it?

Pippa Arend:

I appreciate that question, too. Yeah, from native Portland and grew up at a time when our city was not cool.

Megan Hannay:

It’s hard for me to imagine, because I see it as this hip city.

Pippa Arend:

Yeah. It was always cool to me, but I guess it wasn’t cool to the world yet. I never thought I would stay. My goal in high school was to become a famous expat, and didn’t know for what, and I didn’t know where, but that was my goal and I was going to see to it. After college, I went to college on the East Coast. Small, liberal arts college in Vermont named Marlboro. Then, found myself, I fell in love with an Eastern European that I met. So, I lived in Poland for three years. I did succeed in half my goal. I was an expat.

Megan Hannay:

You became an expat, yeah.

Pippa Arend:

Yeah. I did a lot of welding out there, because at that point, that part of my artistic life had started to merge, but I was not yet famous. That relationship ended in a wildly dramatic Eastern European mafia-esque fashion. I came back in ’95, sort of with my tail between my legs, trying to just be like, what happened? And who am I? Just early 20s querying about life. I came back in ’95—excuse me, ’98, and I found myself in this rush in the middle of this great immigration to Portland of hipsters that were my age. I was just one of them, except I happened to be from this town. It was a fantastic time to come back to Portland as Portland was coming alive in the food and music scene in a way that it just hadn’t before at a time when I could finally appreciate it as well. Knowing this town deep in my DNA, I know every street and every part of this town. It’s deep in my DNA. There’s this great sense of pride and familiarity and all of these things, and yet I was a hipster immigrant myself as well.

Megan Hannay:

Very cool. Final, final question. I know I said that was the last question, but this is really the last question. I just want to bring it back to p:ear a little bit. Obviously, over the past 15 years, working with thousands of homeless youth, what has surprised you the most? If you were to write a memoir, what would be the big takeaway of p:ear so far?

Pippa Arend:

There’s so many ways to answer that. I want to answer that actually with two short anecdotes, one of which was, I was taking kids to see the Nutcracker one night. It was a deep winter night, and we were coming back. We had driven. We were in the van, this little trusty p:ear van. We were just driving back to p:ear, and we passed some street corner, some random street corner, and one of the young women in the car said, just started exclaiming really sadly. My corner is taken. My little doorway is taken. She didn’t know where she was going to sleep that night. I was like, that’s her doorway. At this point, it’s like 10:30 at night. She really knowing sacrificed where she was going to sleep that night because she really wanted to go see the Nutcracker. I said, listen, just tonight, sleep in the doorway of p:ear. In general, that wasn’t allowed just so we could maintain to the best of our ability relatively okay relationships with our downtown neighbors. I said, just tonight, just do that. Just be as safe as you can. Sleep in our doorway. She looked at me and she said, a carpeted doorway? What luxury. She was not being sarcastic.

It just brought me to my knees with this sense of resiliency, gratitude. I felt like it was one of those moments where all of my life’s priorities got rewritten for me. That is something that I don’t even know how to frame in a couple words. It made such an impression. The other moment that really showed me what p:ear means to me personally and what p:ear has become is, a couple years ago, 2010, I suppose, my brother died, middle of the night kind of thing. I heard about it in the middle of the night. I spent the night up with my mother and stepfather and went home, because obviously, I didn’t need to go to work that day. But I couldn’t sleep, and I didn’t want to be at home and I realized I wanted to be at p:ear. So, I came to p:ear, and it really was a moment for me where I really realized, this is my family. This is home. These are the people I want to surround myself with. I suppose that’s just how that day went.

Megan Hannay:

Yeah. That’s amazing. You have a rich number of stories already. Pippa, thank you so much for your time and for speaking to me. P:ear sounds amazing. I’m actually going to be in Portland in a couple weeks, so I’ll definitely swing by your coffee shop at least and get some coffee. Yeah, thank you so much.

Pippa Arend:

Yeah. Thank you.